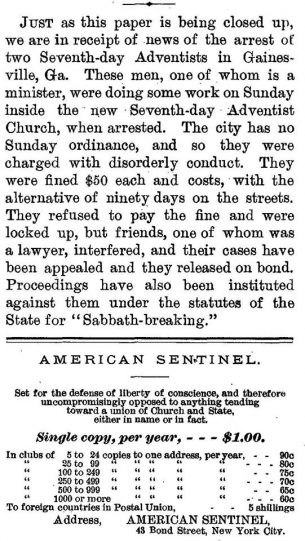

Adventists Arrested For Sabbath-breaking?

As some of you may be aware, this week marks the start of the NAD's Religious Liberty Campaign for 2018. But what exactly is religious liberty? We enjoy most of our religious liberties without much concern due to the right we have as part of being Americans. We have the right to assemble. We have the right to free speech. We have the right to practice our own religion. We have the right to bear arms...albeit swords. Swords. You know...your Bibles...swords. Sorry, bad youth group joke. But in all seriousness, there aren't too many times in our lifetimes thus far that we have had to worry about being oppressed because of our beliefs. But all over the world, people are oppressed, fined, and even jailed for simply professing that they are a Christian. It is true. Sabbath keepers are forced to work on Saturdays because they have no religious liberty.

But not to worry, because we have courts to defend us, right? What if I told you that Religious Liberty is part of the heritage of the Seventh-day Adventist Church? Our story starts off on a Sunday morning on November 19, 1893 on the corner of Pine Street and Longstreet Avenue in what is now known as Midtown Gainesville. On this morning, Elder W.A. McCutchen, a Seventh-day Adventist pastor, and Professor E.C. Keck had some work to do for their church's school by making a few school seats, tables, and other items. They took their workbench into the back of their new church and began working through the morning and then again in the afternoon. They noticed a policeman and another man watching them through one of the windows, but McCutchen and Keck kept right on working and the men returned to town. Later on, there were three men now staring at Keck, who was working alone when McCutchen went back to his house. In a little while, McCutchen returned and so did the policeman who had been there before, along with another. Upon their arrival, the police arrested both McCutchen and Keck and took them to the mayor's office where they were told to appear in court.

Both men appeared in court and were tried for "disorderly conduct". The ordinance read as follows:

Section 268, (adopted Oct. 22, 1891). Any person or persons who shall use loud, boisterous, insulting, or obscene language, or who shall curse, or swear, or attempt to raise a quarrel, or who shall act in a disorderly or violent manner, or show shall fight, quarrel, halloo, or make any unnecessary noise within the corporate limits of this city, calculated to disturb the peace, quiet, or good order of the city or any citizen, shall be guilty of disorderly conduct, and upon conviction shall be punished as prescribed in Section 68.

Section 68 provides for a fine of not more than $100 and costs, or ninety days in jail or on the streets.

The city has no Sunday law at all, but under the ordinance, McCutchen and Keck were convicted and fined $50 each plus court costs of $5, or they would have to serve 90 days in the streets. Both men did not have the money to pay the fines, nor would they have paid it if they had it. Both men were taken to the jail and locked up. Friends immediately went to the courthouse and began to appeal the case to a higher court, but the mayor would make no concessions. A lawyer decided to take up the case and got the men out on bond until January 1894, when the case would be tried by the Superior Court.

Based on the ordinances that the men were arrested, it did not seem that the case would hold in higher courts, but the case continued and before the mayor gave his opinion, a lawyer representing the State asked that the men be turned over to the County Court for...Sabbath-breaking, where the State Code of 1882 provided an "adequate" penalty.

This was a serious conviction for a Seventh-day Adventist being it under a Sunday law. Adventists traditionally refused to pay fines, choosing prison time or working the chain-gangs as a testimony against Sunday legislation. In the State of Tennessee, Adventists who were serving prison time were protected by State Constitution against having to work on the Sabbath as it provided that "no person shall in time of peace be required to perform any service to the public on any day set apart by his religion as a day of rest", but the constitution of this State had no such provision.

BUT...HERE IS THE REST OF THE STORY...

Mr. Keck wrote a letter giving some details:

We were convicted under the ordinance of 1891, and fined $50 and costs or 90 days on the streets. We are told by those who have lived here for some time that similar cases (just convictions of disorderly conduct) are seldom fined more than $5 and costs.

The city had four witnesses against us, all of whom testified that they were disturbed by our noise and work; but in answer to our questions, all admitted that the same work would not have disturbed them on any other day of the week. It was the time the work was done and not the character of the work that disturbed. They said they had been taught that Sunday was a day people ought to keep, and so of course it disturbed their peace to see us working. One witness said he was disturbed before he was near enough to hear the noise. Some one told him we were working and then he was disturbed.

We had but one witness, a gentleman living just across the street, not more than fifty feet from where we were working, nearer than any one else lives. He testified that he was not disturbed. Only one of the witnesses against us lives near the building where we did our work, yet they were all disturbed. All the prominent lawyers were here admit that it was a case over which the mayor had no jurisdiction whatever. As one of them said, if what we did was "disorderly conduct," then every day's honest labor is disorderly conduct.

The mayor in this case was a prominent member of the Methodist church. Because it was found that the city had no jurisdiction in the case, because it had no Sunday legislation, the county court tried the case on February 22, 1894 where the jury, after deliberating for 17 hours, failed to agree. The case was brought up again for trial on August 23, 1894 and was dismissed on the grounds that the labor performed was not in violation of the statue as it was not in line of their "ordinary callings", one being a minister and the other a teacher.

The case would go on Chief Justice Thomas J. Simmons in May 1896 where he ruled that the Superior Court erred in holding that the conduct of McCutchen and Keck was in violation of any ordinance by stating,

To constitute a violation of the ordinance, the act must be such as would be disorderly, and the noise such as would be unnecessary and calculated to disturb the peace, quiet and good order of the community on other days of the week as well as on Sunday. It does not follow that because one does an act which shocks the religious feeling of another, his conduct is "disorderly." People of different religious beliefs have very different views in regard to the observance of the Sabbath, or as to what constitutes a violation of the sanctity of that day. What would shock the religious feeling of one would not be considered objectionable by another...

[The State's] purpose is not to force people to observe Sunday in a religious way or according to the religious views of any portion of the community, but to require that it be observed as a day of rest and cessation from labor, the legislature doubtless regarding this as necessary to the health and well-being of the people. The legislature could have appointed Monday for this purpose as well as it did Sunday, and the law would have been equally binding."

Based on this, judgment was reversed on:

McCutchen & Keck vs. The City of Gainesville

W. A. McCutchen founded the Gainesville Seventh-day Adventist Church in the summer of 1893 and became our first pastor. E.C. Keck was our first school teacher of the school that existed in fall of 1893. This case would be referenced in Religious Liberty topics from that day and even continuing to today.

Sources Cited:

• American Sentinel, vol 8, no 48, December 7, 1893

• American State Papers, pg 720

• Reports of Cases Decided in the Supreme Court of the State of Georgia, vol XCVIII

|

|